Bridge Builder Grace, Patience and Caring Neighbors

Loren Dubberke (SM ’00) and Rogelio Valenzuela come from distinctly different worlds.

Dubberke lived much of his childhood in the fresh air of Mariposa on the doorstep of Yosemite National Park. He graduated high school and earned a bachelor’s degree at Fresno State— expanding his faith and working at InterVarsity Christian Fellowship—before achieving a master’s degree at Fresno Pacific Biblical Seminary.

Valenzuela grew up on the hardscrabble streets of Mendota, an agricultural town known as the Cantaloupe Center of the World and where roughly 40% of the population lives in poverty. He was selling and using drugs by age 12—an addiction that soured his relationship with family, school and the law. The high school dropout hated Christians because he couldn’t understand why they were happy.

Roughly 15 years ago, these two men crossed paths: Dubberke, associate pastor at North Fresno Church, and Valenzuela, a former gang member and homeless father. Their friendship shows the power of faith and Dubberke’s determination to address the stumbling blocks faced by Valenzuela and so many others.

Their meeting was a driving force behind Fresno Area Community Enterprises (FACE), a non-profit helping people overcome barriers and become thriving members of the community. The community benefit organization focuses on education, employment—mainly through three social enterprises—and emotional, spiritual and social support.

“That encounter, along with many others like that—it rocked our world, in the sense of trying to rethink how we respond to issues that are far beyond what we’re trained for,” says Dubberke, the organization’s executive director. “And it also introduced me to larger social and systemic issues that didn’t have quick fixes or easy solutions.”

Since its founding in 2012, FACE’s budget has grown from $30,000 to $300,000, mainly through donors and an annual fundraising banquet.

Fresno Pacific University’s Center for Community Transformation also has pitched in to support social enterprises, which address community problems like poverty and homelessness through business principles.

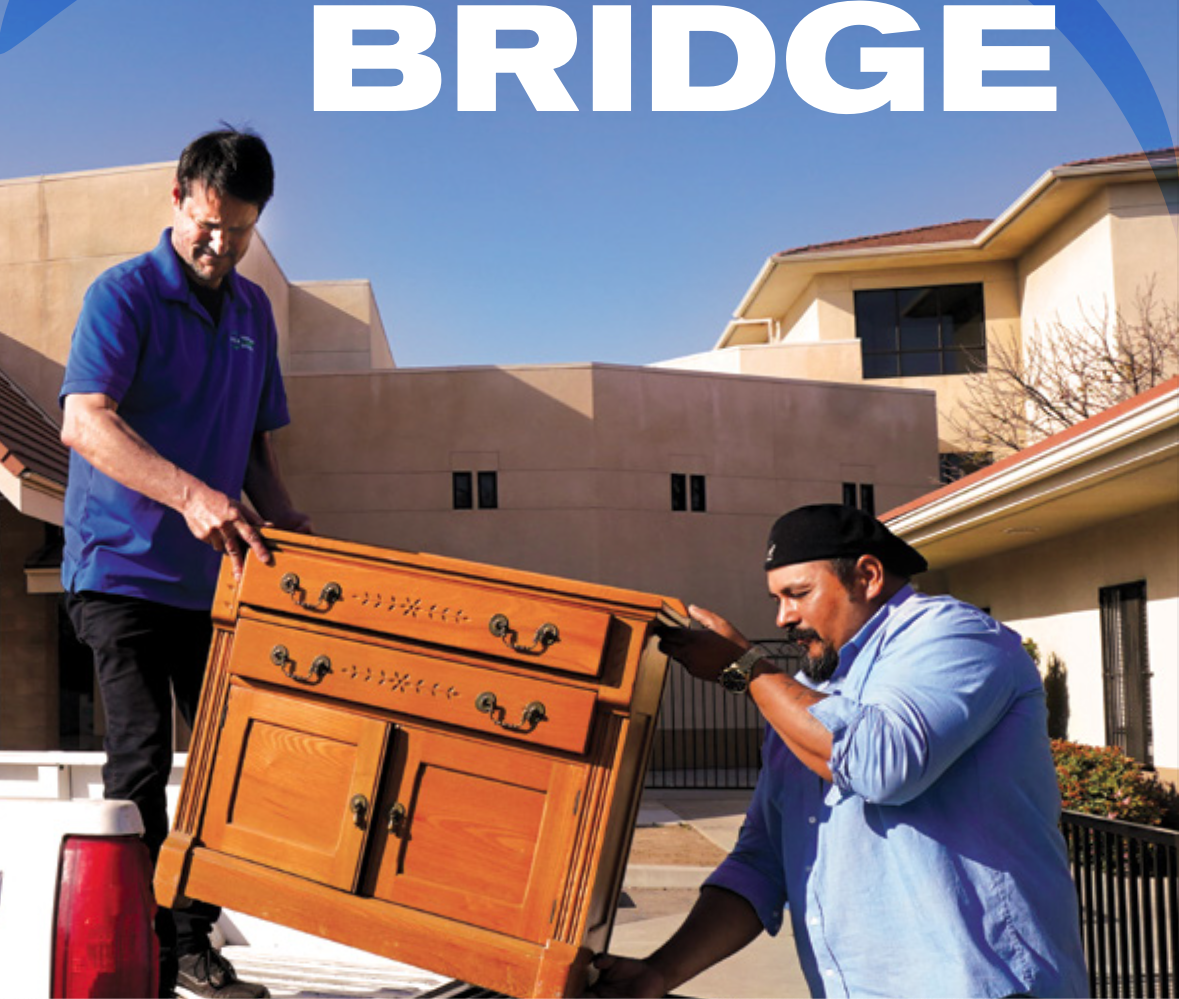

FACE has helped roughly 50 people progress from part-time to full-time employment, frequently via social enterprises like Rock Pile Landscaping and Moving On Up (a moving company). It’s helped countless others identify and achieve goals and develop life skills.

Today, roughly 100 North Fresno Church members are involved in FACE as tutors, volunteers, employers and financial backers. That structure has been a lifeline for Valenzuela.

Today, roughly 100 North Fresno Church members are involved in FACE as tutors, volunteers, employers and financial backers. That structure has been a lifeline for Valenzuela.

“They reflected a kind of love from a family that was unconditional, really unconditional,” says Valenzuela, who calls Dubberke a big brother. “There was always some member of this (church) family that had time for me, a prayer for me, something good to say or who wanted to do something nice with me.”

But his transformation didn’t happen overnight. Back in the 1990s and 2000s, when crime was escalating and Fresno was struggling for answers, city leaders encouraged churches to adopt troubled apartment complexes like Whispering Woods, a densely populated cement jungle near North Fresno Church.

The outreach was exactly the challenge Dubberke sought. “I wanted to not just work inside the walls of the church, but outside in the neighborhood,” he says. “I wanted to be a bridge builder.”

He began shepherding efforts to serve the neighborhood around Robinson Elementary School in north Fresno, which struggled with unemployment, poverty and other challenges. A reading club was in place at Whispering Woods; Dubberke brought in college students as tutors and started a sports club for the hundreds of kids living in the complex.

Slowly, the harsh reality of that world emerged. “Pastor,” a child would say to Dubberke, “did you know that Johnny doesn’t have a bed?” Or another family didn’t have any furniture. Or another couldn’t pay the electric bill.

He and the church provided bags of groceries, cash for the power bill or bus tokens and other emergency aid. As requests flooded in, the church formed the Social Action Response Team to sort through the cries for help.

And then there was Valenzuela. When the two men first met, Valenzuela was homeless and weighed down by a record of incarceration. He lived in an old Cadillac with his three young children in the Whispering Woods parking lot—and that was just the first of many problems.

A friend gave him Dubberke’s phone number, and Valenzuela was surprised when he answered. They talked and met the next day, where Valenzuela opened up about all of his troubles with the law, the volatile relationship with his wife and more.

Afterward, Valenzuela was hesitant to trust the man he thought looked like the “Where’s Waldo” character. He worried that Dubberke had leverage—his history—that could be used against him.

But Dubberke only listened and began by attacking the family’s most immediate need: housing. There was no shelter for men with children in Fresno, so church members located temporary housing vouchers and helped drive the children to and from school.

Valenzuela stabilized—temporarily. Trust issues, and the pull of his old life, led to an up-and-down cycle that Dubberke remembers too well.

“I’ve almost thrown in the towel because of situations where I see someone relapse after giving so much,” Dubberke says. “He tested me in terms

of my patience and what it means to really stay committed to someone through thick and thin, and how you love someone continually even when they are making choices that are harmful.”

One morning about five years ago, Dubberke spotted Valenzuela in the church parking lot wearing a bright jail uniform. He’d walked all night to get to the church following his release, and this time he was invested in change.

Valenzuela found housing and a job with the FACE landscaping service. He stayed out of trouble by staying busy. Valenzuela’s renewed commitment to a Christian lifestyle and the church led to a job in the mountains related to wildfire reduction.

For the first time in a while, he was reliable— and that translated into an opportunity with an electrical company. Now, Valenzuela is working toward his landscaping license and residential electrician certification. He is, finally, a success story.

“This kind of work is long term, and it takes a lot of relational, emotional, social and spiritual investment,” Dubberke says. “He’s definitely an example.”

Valenzuela wasn’t the only one who grew in this journey. Dubberke says he learned valuable lessons about street smarts, the struggle of incarceration and the difficulties of substance abuse and trauma. “I think a lot of us don’t know how hard it is sometimes to get out of that cycle,” Dubberke says. “He’s taught me a lot about resilience and adapting and perseverance—and faith, too.”

Valenzuela wasn’t the only one who grew in this journey. Dubberke says he learned valuable lessons about street smarts, the struggle of incarceration and the difficulties of substance abuse and trauma. “I think a lot of us don’t know how hard it is sometimes to get out of that cycle,” Dubberke says. “He’s taught me a lot about resilience and adapting and perseverance—and faith, too.”

Valenzuela, now 44 and the father of six, is engaged to a former schoolmate. They reconnected on Facebook, and she is one of many people who prayed for him during his childhood. Valenzuela used to bark at her to leave him alone, but now he appreciates the power of prayer.

He calls Dubberke “my rock” and someone he turns to for advice—even if he didn’t always take it at first. In turn, Dubberke calls Valenzuela a friend and “a walking example of what we hope everybody could do—except that it took him 15 years. It’s really a story of restoration and hope, and that’s what we’re about.”

About FACE at facefresno.org